Level: Apprentice

Reading Time: 15 minutes

Here's where I am coming from. I made a batch of 73% chocolate using the Lam Dong beans from Vietnam. The tropical fruity taste and tangy hints are excellent in this chocolate. It peaks about 4-5 seconds after placing it in your mouth and lasts about 4 seconds - it was heavenly. However, I found this fruity tang peaked on the second or third day after making the chocolate and then declined in intensity after that. I had placed the batch in a plastic container and sealed it but there was a lot of air space. So, how do you preserve this little piece of heaven? Tighter sealing? Freezing? or just accept it does not last long? I checked your answers, and did not see anything on storage of chocolate.

You accept that it does not last. Like most really fresh products, fresh is best.

I really could end the conversation there but it is quite unsatisfying because as I say it I picture lots of things in my head. Complex interactions of chemicals, how those change over time, our perception of those flavors and how all of it is a dance that makes me eager to show you what I see behind the curtain.

There is too much ‘because I said so’ in the world. It was not satisfying when I was 8, it isn’t any more satisfying now, and I can’t imagine ‘it does not last’ is satisfying to you either.

That said, if you are happy with that answer, then great. Stop there and be happy. I’ll let you know that eventually the taste of your chocolate will eventually stop radically changing and that will be that. For those not satisfied with that answer, let’s have a little peek inside my head as to how I imagine what is going on inside the chocolate.

Warning - moderate science and graphs ahead.

Before I dive too far in it is important to realize that I am trying to get some concepts across to you and if you try to over analyze what I am saying and showing it very likely won’t make sense or be internally consistent. It is sort of like dream logic. At the time it makes perfect sense but as you pick it apart….things get funny. Ok? Good.

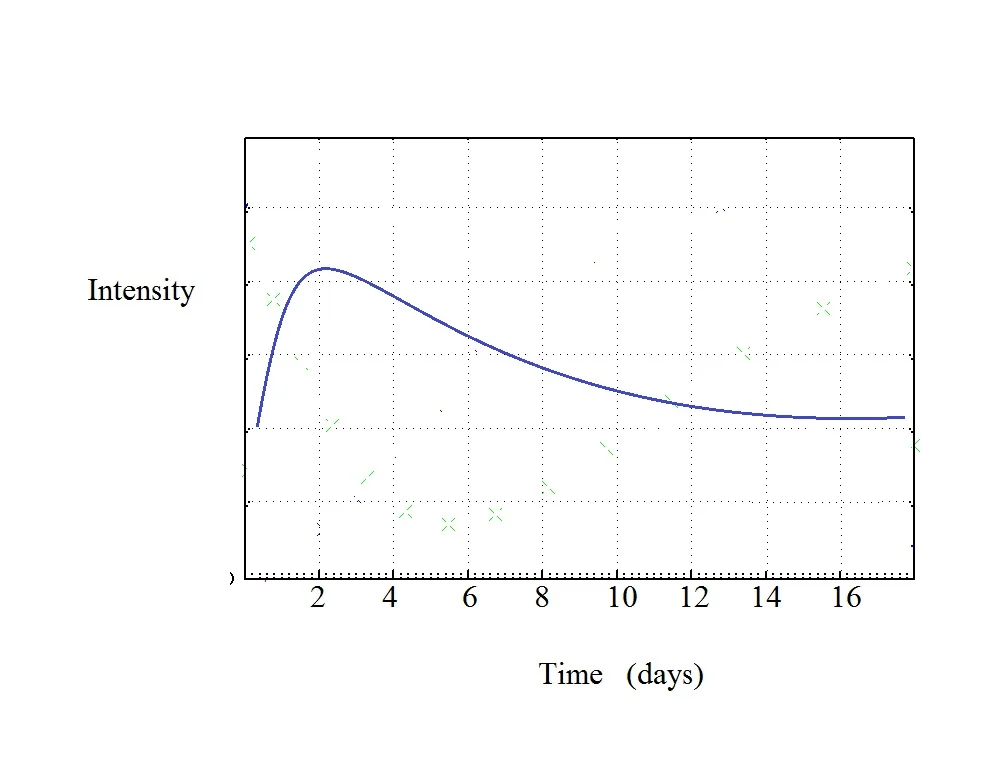

Let’s plot what you are saying and what I see when you say that it peaks and then declined.

I have no idea what the units for intensity are but in our dream it does not matter. The main thing to note is how the curve goes asymptotic to a final level. It goes into a steady state. It is stable after some amount of time. Asymptotic just mean the lines becomes nearly flat. Your problem is that you like the chocolate before it reaches its stable flavor profile.

You asked about sealing it or freezing it. First off sealing it won’t do much good. Lots of chemistry is going on inside your bar and free oxygen from the air has little effect on the interior chemistry.

Freezing though. My apologies for being a touch pedantic here, but what you really mean is putting the chocolate in a temperature below the freezing point of water. Your chocolate, having set up, is already ‘frozen’ since it is a solid. Yeah, semantics, but it is important and I will get to that in a bit.

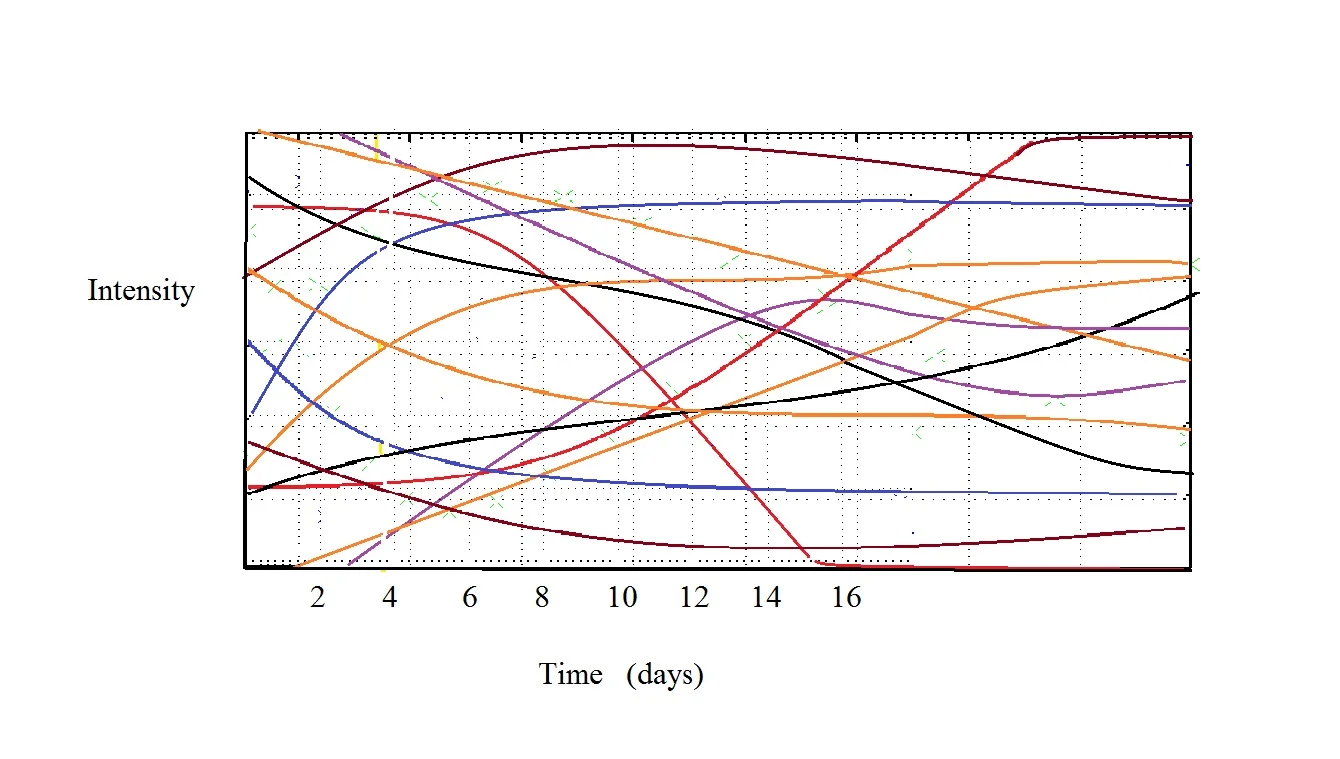

Your chocolate is changing how it tastes because chemistry is happening. Some chemicals are going up, some chemicals are going down. There probably isn’t just one ‘fruity tang’ chemical that is first going up and then decreasing. It is most likely a whole host of compounds so your simple intensity vs time plot really looks more like this.

This shows three different chemicals. One is falling over time (red), one is increasing over time (blue) and one (purple) is (in my dream) being created by red and blue reacting and then eventually dropping off after red is used up. And that is even very simplified. In reality there are dozens if not hundreds of compounds changing subtly over the first few days and weeks.

Before your eyes glaze over just keep in mind I’m merely making a point that it is complex. The take away is that for a given time, there will be a slightly different amounts of different chemicals and depending upon their ratios you may or may not taste different things. But the key is that very, very rarely is one flavor controlled by one chemical.

Getting back to freezing, or more specifically, storing your chocolate at lower temperatures, we get to talk about something called rates of reaction. It can sound a bit complex but it is really no more complex than talking about speed. Miles per hour. In rates of reaction you track concentration instead of miles and usually seconds instead of hours. So it is just a measure of how fast one particular chemical’s concentration changes over a given time.

Freezing as it were, you know intuitively, slows down the reactions and how quick the concentrations change. You know this or you would not have suggested it.

There is even a simple rule of thumb that can be used. It is: for every 10°C increase, the reaction rate doubles. The corollary to this is that for every 10 C decrease the rate is cut in half.

Room temperature is generally defined as 25 C. If you store it at 15 C reaction speed will be cut in half. 5 C (refrigeration temperature) and it is half of half or 1/4. -5 C brings us to 1/8. So if you store it at -5 C you have 8 times as long before the flavor changes, right?

Not really.

The immense catch here is that this rule of thumb is talking about a gas or liquid phase reaction. Remember when I said your chocolate was already frozen, and that it was a solid. This is why it was important.

Reactions in solids slow WAY down. But they do occur or you would not be noticing a change over time in the flavor. What that means is that it takes very little energy to let them proceed. Whereas reactions in gases and liquids are cut in half by a reduction on 10 C, solid state reactions change in proportion to their absolute temperature. Yeah, that is getting a touch technical. Let's walk through it.

Room temperature is 25 C. But it is 298.15 Kelvin (25 + 273.15 is the calculation). This is the absolute temperature scale. To slow reactions down by half you have to reduce the temperature by half to 298.15/2 or 149 K. That is (149 - 273.15) about -124 C or -191 F. Most freezers go to about -5 C, about 30 C under room temperature. That means by putting your chocolate in the deep freeze you can slow the change about 11% (30/273 = 0.11). Hardly any at all. An extra 5 hours in this example of a peak at 2 days.

But let’s go crazy. Let’s store your chocolate in liquid Nitrogen at -195.8 C. That is about 74 Kelvin. 74/273 = 0.271. That close enough to saying it is slowed to 1/4 of the original speed (0.25 = 25% = 1/4). Not too bad. You do that and come back a week later. You are within your window of it tasting about the same. You unwrap it, let it warm up a bit so you don’t freeze your tongue, taste, and……..it does not taste the same.

Crushing disappointment.

What happened? Remember I said there was a rule of thumb? 10 C for half the speed for liquids and proportional with absolute temperature for solids. They are just rules of thumb. On average the reactions may have slowed to 25%, but the reality is that each of those reactions are different and some may be 20%, some 35%, some only 50%. And some might even totally stop all together. The result is that at the end of your chocolate's stay in the deep freeze you didn’t slow the march across the graph - it changed the shape of each curve and the final ratios.

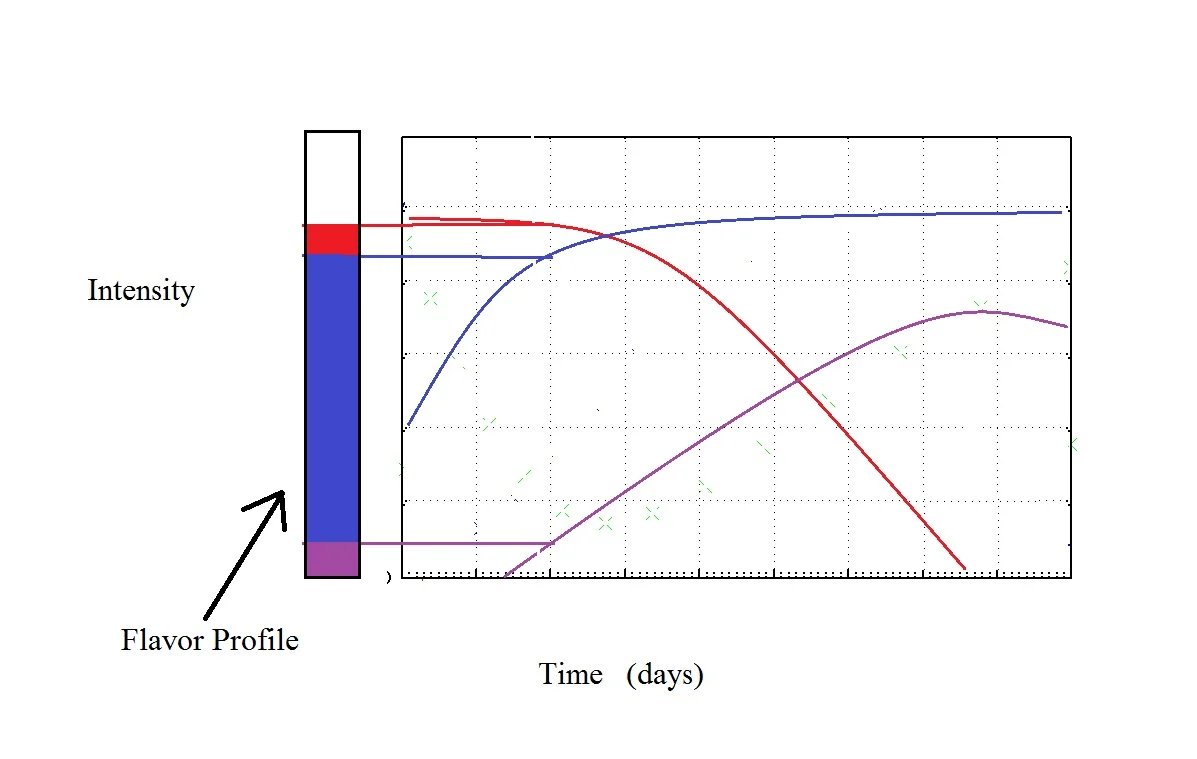

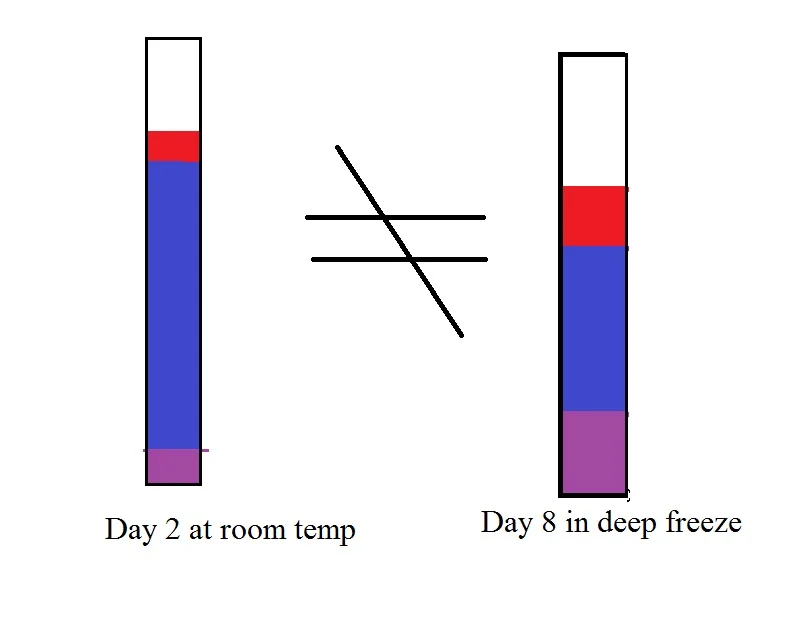

I realize that may be a little hard to wrap your head around. Look at this:

Think of what you taste as a picture. That Flavor Profile is what your chocolate tastes like on Day 2. Each color just represents the relative concentration of each chemical. To taste the same it has to look the same.

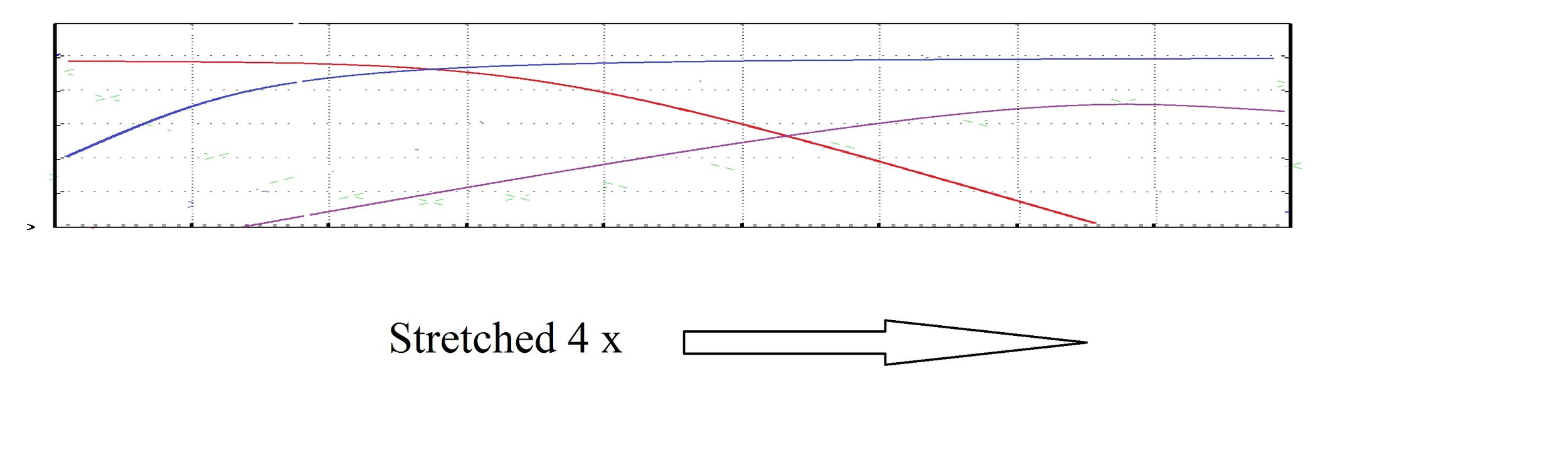

So now we are going to put the chocolate in the liquid nitrogen deep freeze and slow everything down. Basically we are going to stretch the graph. It would look like this:

Unfortunately that isn't what it would look like. The rates of reaction shift somewhat and you get this. The new rate is the thicker line.

The shapes are basically the same, but different enough that ratios shift. There is a lot less blue per red and purple. If you compare the two Taste Profiles you can easily see they do not look the same.

Chemistry is messy and complex. And really no temperature change is going to keep those ratios exactly the same and the flavors predictably similar. All you get if you freeze chocolate is cold chocolate. And for you coffee aficionados out there, the same holds true. Putting your fresh coffee in the freezer just leads to stale cold coffee.

So what can you do? Sadly I don't have an answer. At least one that lets me offer suggestions as to how to get what you want. The closest I can offer is to suggest that you wait at least a week before tasting your chocolate and then adjusting your roasting and recipes to come closer to what you want. Basically wait until the majority of the chemistry is done and not changing quickly on the fly.

For such a simple question I know that twisted and turned quite a bit. Welcome to what I think about and how I think about things when people ask me questions. I hope it shows just a little about how complex chocolate, and well, most everything can be. It can actually be a little paralyzing, but my hope is that it shows why in many cases there simply are not clear cut answers to a lot of the questions you have.

That said, if you want more fruit, roast a touch lighter and if you can refine a little cooler. It is where I would start.....or if you roasted very light, maybe you need to be more aggressive with your roast to create more of the fruity compounds. See what I mean, no set answers.