Ask The Alchemist #181, Question: Have you ever tried tempering chocolate with a Sous Vide?

Viewing entries in

Tempering

Ask The Alchemist #180, Question: Have you ever tried tempering chocolate with a Sous Vide?

Level: Alchemist

Reading time: 20 minutes (if you are lucky)

Question: Time? Things are considered tempered when you take a test strip cool it and it has the characteristics you want. My question is does this happen rapidly, say 95% of the fat is in “V” at 10 mins, or is “tempering” when say 50% of the crystals are in the correct form. Does extending the time at temperature to say a day or 2 get significantly closer to 100% in V? Does this make a difference? You probably reach a point of diminishing returns, just curious how much science has been applied to this voodoo…

Funny you should mention voodoo. As I am going to take this into the exact opposite direction and define tempering in technical terms.

It’s worth noting that as I think of all I want to convey I feel like the philosopher who has attained enlightenment from the study of a butterfly wing and now wants to convey it to everyone….and takes page after page explaining it and ultimately fails because you usually can’t explain deep concepts quickly or easily. Regardless….onward.

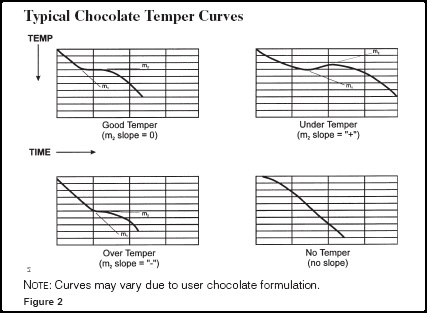

Chocolate is tempered properly when the inflection point of the of a temperature vs time cooling plot has a slope of zero.

And I suspect that doesn’t mean or explain anything to most of you. If you have a look around the internet you will find this old school image pretty quickly.

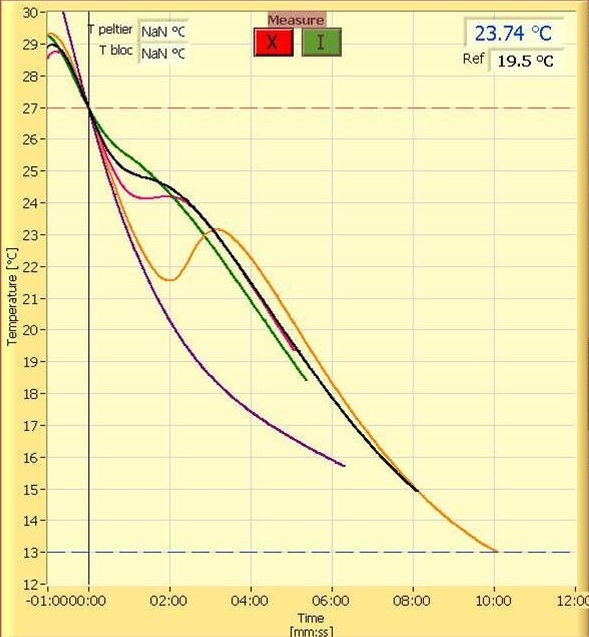

Digging a bit deeper and you can find something like this that shows real data in a form more of you can relate to.

In both cases they are showing plots of chocolate in different stages of temper, from untempered all the way to over tempered.

And I want you to read that last line again. There is something very important there that takes many people many years to realize. The first epiphany as it were. Over tempered. Chocolate can be over tempered. Understandably a large number of people think you want 100% temper. All Type V crystals. But that isn’t the case. You want a balance.

So that answers a part of your question. Or more to the point, it sheds some light on some of the assumptions you have made about tempering. That it is an end state. Sort of like absolute zero. And maybe it is. The key here is understanding that IF the perfect temper is analogous to absolute zero, then your goal is NOT absolute zero, but some temperature above that.

Try and let that sink in. I’ll try and explain why that is at the end.

But before we get deep into all the revelations that those plots can give us, let’s take a few moments and talk about what you are seeing there.

WARNING – SCIENCE AHEAD

Pretty much all of tempering is predicated on the concept of crystallization.

The following concept is one you need to wrap your head around.

Solidifying fat crystals give off heat in the same way dissolving salt crystals take in heat. These are the two sides of the same coin or concept.

That doesn’t make sense? This puts it into tangible terms.

If you make ice cream the old fashion way, you will recall you mix ice with salt. Remember that? Do you know why? Solid salt is just sitting there. It has low energy. Salt in solution is moving around. It has more energy. That energy has to come from somewhere. In the case of your ice cream and ice, it comes from the temperature of the system. Ice cream, ice and salt separate are all at 32 F. If the salt needs energy to dissolve, then it has to steal it from somewhere so it takes it from the only place it can; the temperature of the ice cream and ice. The result is that those temperatures drop to something under 32 F as the salt dissolves and your ice cream solidifies.

Got that? The whole point is to melt a crystal it has to take in heat. Therefore the opposite is also true. To form a crystal, heat is given off. This heat is called the heat of crystallization. To go all science and geeky on you:

“Heat of crystallization or enthalpy of crystallization is the heat evolved or absorbed when one mole of given substance crystallizes from a saturated solution of the same substance.”

Let’s bring this back to chocolate and set the stage. You are in the process of tempering your chocolate. You have either made or introduced seed to your untempered chocolate. For the sake of discussion, let’s call it 31 C. You pour it up into your mold and it starts to cool and eventually set up.

If we peek behind the curtain, and can monitor the temperature and crystals we are going to see the temperature start to drop. That is just the natural cooling of the chocolate. Energy is being given off to the atmosphere or maybe your refrigerator. At the same time, the seed of Type V crystals are going to start propagating or growing.

And now the fun part (did I mention I’m a retired chemist who finds this fun?).

We can make a prediction. As the crystals start to form we know (see above) that they are going to start giving off heat to the surround chocolate. And what is that going to do?

Very good. The temperature is going to rise.

And if we record those temperatures and the time, and then plot them, what is it going to look like? It is going to be a decreasing line (the temperature is falling initially because it is in the refrigerator or whatever) then, (oh, I’m so excited) since those crystals are giving off heat, (I’m virtually giddy here) the line is going to level off or maybe (shaking with geek excitement) even go back up! Then, once all the crystals are formed and no more heat is being evolved (yep, pulled in a science word there) the temperature will continue to drop to whatever the ambient temperature is.

Do you have that image in your head? Hopefully, it looks a LOT like this:

Which, wow, looks pretty much identical to the plot at the beginning for properly tempered chocolate!

Science!!! (giddy again….calming down…. )

Okay, I’ve calmed down for the moment. Hopefully you have the concepts down and we can talk about what they mean.

The first thing I want to address is that a zero slope (that flat spot) is nothing special. It is empirical meaning that it is just lucky coincidence that the majority of we humans like our chocolate when it is tempered at a zero inflection.

If you go back to the top and have a look at the curve of untempered chocolate you will notice it is basically a straight line pointing down.

“But alchemist, even bloomed chocolate has crystals. Type III, IV and V. Don’t they have a heat of crystallization and wouldn’t they cause some heat rise?”

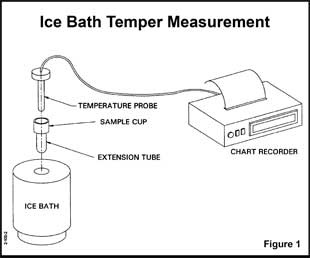

I am proud of you for making that connection. It is 100% true. IF…and this is where I didn’t play straight with you…we were truly measuring the temperature of your chocolate as it set up. But that is not what those plots are from. They are actually from a special setup that measures the degree of temper in a chocolate. It basically looks like this:

This image and the text below on It’s workings is from Ticor systems

“Their operation is quite simple. A cup-like opening at one end of a long metallic (copper) tube is filled with a chocolate sample. The other end of the tube is inserted in a mixture of ice and water held in an insulated container. A temperature probe (thermocouple in early versions) is then inserted into the chocolate. Since the chocolate sample is above 85°F and the sample holder is attempting to reach the temperature of the ice bath (a questionable 32°F), the chocolate gives up heat to the holder and is cooled to solidification.”

The key difference here is the ice bath and that in a degree of temper analysis you are forcing the chocolate and temperature down quickly along a reproducible path (because is a constant temperature and the system is insulated). The consequence of this is that you can see deviations easily and you are literally forcing the chocolate to solidify without crystallizing. Because no crystallization is happening, no heat is given off and no rise in temperature is noted.

Got it? Good!

And now we can talk about some of those bits of enlightenment that fall out of these graphs.

If you look at the 2nd graph above with all the overlaid plots you see a spectrum of non-tempered curves all the way to over tempered. This means tempering is a continuum and what falls out of that is that tempering is not a discrete state but a process and because we can have a full range of tempers we can have variables that we can adjust in a predictable manner to give us those final degrees of temper.

What are those variables? Well one big one should be obvious. The amount of Type V seed you have present and the original question hints at that. And that makes sense. The more seed you have, the more energy that is given off in a set amount of time and the more the cool curve tips up. Likewise, if you don’t have enough, it doesn’t tip up enough, the slope of the line doesn’t make it to zero, and you have under tempered chocolate, and if it is under tempered too much, it can bloom.

So, is time something you can manipulate? Will more time (2 days?) give you a higher degree of temper because more seed is formed? It certainly seems like it might be, and it can be, but it turns out that it isn’t practical. And the key is understanding that time is only helpful if it is your only variable. And in many cases it isn’t.

If you are tempering from scratch it is useless. Why? Because when you bring your chocolate down to 80 F or so and form seed, how much you form is varies with how fast you reduce the temperature and the ambient temperature. Without being able to control those exactly, you will have different amounts of seed (which you have no way of knowing) and that basically means you are starting from a different point in the tempering process each time so you can’t get to the degree of temper by measuring time.

If that isn’t clear, think of it as getting a car up to 60 mph (perfect temper, zero slope inflection) from a random unknown speed with only a stopwatch. It can’t be done. There are too many variables. How fast are you going (how much seed initially), how much are you accelerating and how do you measure it (what is the ambient temperature) and are there hills that you have to go up or down (how much heat loss do you have).

This is why hand tempering can be a series of failures until you both get a feel for how fast 60 mph is and you get used to the road (i.e. your techniques and conditions get VERY reproducible).

So what are you to do? You use some form of seed. And a tempering machine or water baths if you can. Neither is magical. They are nothing more and nothing less than variable control and management.

When you use seed or silk you starting with a known amount of seed, and better yet (analogy shift warning) your speed IS 60 mph and you just have to maintain it by watching the speedometer (your temperature).

If you want a lower degree of temper, you use less seed/silk. If you want I higher degree of temper, you use more. That simple.

So, it was probably hard to miss that I mentioned both seed and silk. The distinction is that the former is tempered chocolate and the latter is tempered cocoa butter. And they produce different tempers. Not just different degrees of temper, but actually different types of temper.

S. Beckett (The Science of Chocolate) notes this:

The temperature at which the inflection on the curve occurs is very important. The higher the temperature the more mature the crystallization and the higher the temperature at which the chocolate can be used for moulding and enrobing.

Silk makes for a more mature crystallization and is my personal favorite way to temper (video of that coming up). You can see this by how it is used. You mix it in at around 93-94 F. You use significantly less (0.5-1%) than you would tempered chocolate (20-30% many people recommend) and it propagates very fast through the chocolate, setting up quickly and with a particularly high resistance to blooming. And if you were to run a cooling curve on it you would see it produces the inflection point at a higher temperature correlating with a more mature crystal.

Is this all helpful day to day? I personally think it is since I wrote it. How? I think 90% of the help it gives is taking some of the mystery out of tempering (after you reread it a few times). It is just variables and if you grasp that, you can start to look for variables in your process and eliminate them or at least identify them when something goes awry and you chocolate blooms.

Can your or should you set up your own temper meter? If you find it fun and like the hard data, by all means do it. It isn’t hard. It is basically a thermometer and an insulated ice bath. You will probably have to play around a little with your sample size to get a flat line for untempered chocolate but that is about it. But of course you don’t have to. Hell, I LOVE this stuff and have not done it. But you can.

Oh, one more thing.

Remember I said I would explain why you don’t want an absolute temper? It’s really kind of simple. Mostly it is because you are a person eating chocolate and not a chemist striving for a perfect beautiful crystal. You are not looking for perfection in structure. You are looking for perfection in mouth feel. You are looking for an experience. You are looking for that perfect state where the chocolate is smooth and melts easily in your mouth. That point of state that allows maximum release of flavor and enjoyment. You are looking for the perfect tipping point where it is almost bloomed and almost too hard.

You are looking for balance.

I hope that was enough science to this voodoo we call tempering.

Welcome to the art AND science of chocolate making.

Level: Alchemist

Reading time: 7 min

So I have the revolution X chocovision tempering machine.

I am noticing at our apartment temperature being an average of 74F our chocolate does not hold nearly as well as others. I have a bar from fruition, rogue, dandelion, etc etc all at about the same 70% ratio and they seem to hold their temper so much better. Some don't use any cacao butter while others I can tell by texture use quite a bit.

I use these big blobs or "brains" I call them for seeds, I use them over and over but they are all white and flake apart when I put pressure on them... Is it because they aren’t in perfect temper why the resulting chocolate isn't coming out and holding that glossy black temper for a long time?

I just notice it gets a slight white film on it after a few weeks and the texture gets a tad funky..

Just so you know I am also using the temper 1 setting, so seed out at 90F and molding at 88.7F and then in the fridge to harden.

Should I be using the temper 2 setting where it drops it down and then back up to 88.7? Since the quality of my seed is pretty shit? Just figured I would ask. I am going to experiment as I just read through your illustration of tempering (great job by the way, the best most clear description I have seen yet)

If I just let the chocolate sit at room temperature it comes out really streaky and white

I figured 74F is just too warm, but based on your illustration it seems the temper might be off?

OK, tempering troubleshooting it is today.

For those not sure what is going on here, the method here is a mixture of a way I found works under certain conditions and using a tempering machine with seed. You can read the whole method here. http://chocolatealchemy.com/illustrated-tempering/

It entails using freshly crystallized chocolate as seed for tempering. Go read it. I won’t bore you here repeat it all.

Your issue appears to be that you have combined methods and are storing and using old bloomed chocolate instead of the freshly solidified chocolate that I call for. That is clear, aside from you saying it of course, is because it is white and crumbly. Forget “not perfect temper”. These are fully bloomed and devoid of any temper. Just because you call it seed does not seed it make.

The key to making my method work is that the seed portion that you use must be relatively fresh. In this state, there is a lot of Type V crystals. When you put this into your melted chocolate at 90-95 F, all the other types melt and you are left with a substantial quantity of Type V that acts as real seed and you get a good strong temper.

In old bloomed chocolate the amount of Type V has gone down significantly. As bloomed chocolate ages, there is solid state conversion. Type V converts to both IV and VI under certain conditions and this most likely is what is causing your issue. Those blob/brains are your indicator that your have Type VI. The Type VI melts at even a higher temperature than Type V, so there is no way to get rid of it without destroying your remaining Type V also.

I can’t really speak for your tempering machine’s settings as I don’t know them. Regardless, going down to 80 and back up won’t fix your issue if you are using Type VI contaminated seed unless you go all the way up to 100 f and then back down, which negates the whole reason for seed.

My recommendation then is to toss your crumbly not-seed chocolate and start fresh. And after that, instead of using this current method, there is no reason not to just reserve a bar of well tempered chocolate as your new seed.

Level: Apprentice

Reading time: 10 min

I am struggling making my 70% chocolate with only two ingredients. It seems like what I should do but it is really thick and hard to work with. It blooms really badly. What am I doing wrong?

Why are you not adding a little cocoa butter?

I mostly keep my head down in social media but I’ve heard through various grapevines that two ingredient chocolate is becoming a *thing*. And I completely do not understand it. It is talked about like it is superior or the maker is superior for using only two ingredients.

I guess I am going to soap box here a little, and I don’t mean to offend anyone in particular. Just take it as my musings on the subject.

It seems maybe this is where you are getting the idea you should be using only two ingredients. Cocoa beans and sugar I assume. Trying to suss out why, people toss out phrases extolling the purity of flavor or staying true to the cacao or other such nebulous statements. At the end of the day, it feels like marketing. A way to set themselves out from the crowd. Ok I guess.

If that is what you like, by all means make it. But I caution the thinking that using only two ingredients is in inherently better. By what metric? Sure. Few people want to eat a chocolate with 27 ingredients where 95% of them are chemical names. But once you are out of that mindset, I don’t truly get how 2 is better than 3 or 4. Why not 1 ingredient?

But to my way of thinking, it is some kind of pendulum reaction to 27 ingredient chocolate product. That if that is considered inferior (no real argument there) then the absolute bare minimum must be the best. This is the same logic that raw chocolate folks make. Over roasting is bad, so no roasting is best. That’s bad logic and the world does not work that way. Too much food (obesity) is bad so no food is best? Really? It is the same logic and makes as much sense. None.

Going back to metrics and why two ingredients are better I would propose these two metrics for consideration.

1) Adding a little cocoa butter (2-3%) to you chocolate can actually enhance the perceived flavor of the chocolate. It does this by allowing the chocolate to dissolve faster in your mouth, creating the sense of more flavor. You are familiar with this phenomenon in regards to sugar. Which seems sweeter? Rock candy or granulated sugar? Both are 100% sugar, but the granulated seems sweeter since it can dissolve faster.

2) Two ingredient chocolate can be thicker, and more temperamental to temper. How does this make it better? It doesn’t.

It is also worth noting that in conversations with supposed two ingredient makers, well over half say they used *a little* cocoa butter in their melangers to make life easier…..which suddenly sounds like 3 ingredient chocolate to me. This more than anything makes me think they are just playing a marketing game and that it really doesn’t matter.

That all said, let’s see if I can help.

First off, I am going to recommend you reconsider why you want to use only 2 ingredients. Put aside what you see other people doing. Keep in mind that that two ingredient chocolate you tasted and love *may* contain extra cocoa butter. Evaluate the chocolate you are making for what it is. Did you actually try making it with a little extra cocoa butter and if so, did you like it better without added cocoa butter? And why didn’t you make 1 ingredient chocolate if you wanted to *pure* cacao flavor?

Seriously, this is about what you like and enjoy. And that means the process too. If you can’t temper it because it is so thick, and it blooms, and you didn’t like the chalky texture, just how did you improve the experience and/or final product by keeping it *pure*?

Ok. I was going to offer help. I have heard that people have had difficulty with Tien Giang being especially thick. So I roasted 6 lbs and divided it into 3 batches.

1) The control. 74% cocoa, 26% sugar.

2) Heated control

3) 20% vodka soak

Spring boarding off my success with the honey chocolate, I mixed in vodka 20% by weight into the roasted nibs. After soaking in for 2 days, I dried them in an oven for 2 hours at 150F. To make sure it was not just the heating that made any difference, I also heated an equal amount of roasted nibs the same way. My hypothesis here was that moisture was causing the extra thickness and that by reducing that moisture, I could reduce the viscosity.

The final results were everything I hoped they would be.

1) This was thick and very hard to work with.

2) This was thinner and easier to work with.

3) This was the thinnest of the three.

The extra drying helped significantly to dry out the nibs, even though they had been previously roasted. In many cases I think this might be all you need to do if you insist on only 2 ingredients.

The vodka really helped to pull out extra moisture. I took weight measurements before and after drying and out of 740 grams of nibs, the heated control lost 5 grams of water, and the vodka treated lost 12 grams.

And the flavors were basically the same.

Alternatively, 3% cocoa butter reduces the viscosity nicely and if you are not allergic, 0.5% lecithin will very nicely bind with the water and make the chocolate easier to work with. And to my tastes, they all taste just as *pure* and true to the cocoa’s potential. Your mileage may vary.

If you have not guessed, I lean toward solid data and rigorous evaluation. Don’t follow a path because everyone else is. Make what you like and be honest about it and challenge your per-conceived notions. Maybe they will be right….but maybe you will find there was a heavy placebo effect going on and that 2 ingredient chocolate isn’t anything particular special.

Chocolate you made yourself. That’s special.

Level: Alchemist

Read time: 6 minutes

I have been bowl tempering with good success until the ambient temperature in my kitchen went up. Typically in the morning when I temper the kitchen is about 60 degrees. We had some unusually hot weather and we have no air conditioning, so my kitchen was about 80. However, knowing this I took my liquid chocolate directly from the melanger, cooled it with a bowl of 65-degree water to 79 when it started to thicken, then immediately put it into a bowl of 100-degree water and slowly brought it up to 88. The molds then went immediately into a 45-degree refrigerator for 30 minutes, and then into my basement where the ambient temp is about 70. It’s with a bean, Bolivia, that I use a lot and my normal formula and melanging time. Yet the finished product had a soft temper. It was OK but I would not call it a full temper because it was softer than usual. It did not have the same snap and when you laid one bar on top of another it did not have that satisfying click. With this close control over my temperatures why did that 80-degree ambient temp have an effect on it, when the chocolate was not left at that temp at any time? (I even melted it down and re-tempered with the same result). Seems like I am not getting enough type 5 in there but can’t figure out why.

This is a really great question and I have to admit had me stumped for a little bit. You are correct, it sounds like everything should be working perfectly. Yet clearly it isn’t.

When I first read this I had an idea what it might be, but I needed to ask a few question In order to suss out.

It turned out that when it was not as hot, the molds hung out on the counter a little while since there was no rush to get them out of the heat.

This difference, the time on the counter, between going into the mold and chilling in the refrigerator, was the key.

Most of the time this time does not matter. But it can matter. Clearly. The problem was not so much that there was not enough Type V. It was that there was not enough time to allow it to do it’s job. By going from 88 F and a nominal amount of V, it was plunged straight into the equivalent of deep freeze. The Type V didn’t have time to do its job and propagate throughout the chocolate. Basically it was flash frozen. And the result was a soft temper.

Chocolate needs a little time for the Type V matrix to form. Just 5 or 10 minutes will often do the trick. At 80 F, as in this kitchen, it might have needed 15-20 minutes. The other alternative, which quite a number of chocolate makers use is to use a cooling cabinet. Those are cool, say 50-60 F, but not really cold. They give the Type V time to spread throughout.

In your case here I would have just taken the chocolate straight down to the basement where it was 70. Or alternatively, just left it in the 45 F refrigerator for 5-10 minutes. Not enough to flash freeze it as it were, but to take the edge off, get it cooling and crystalizing but not too fast.

And if you don’t have that 70 F basement, and the refrigerator is all you have, you may just need to wait out the heat. Chocolate can be a demanding and finicky lover.

So, in these warm days of summer, do keep that in mind. It’s still all about balance. You have to hit that Goldilocks zone. Get the chocolate chilling, but not too fast and not too long as you can have too much of a good thing.

Good luck and try to keep cool.

Level: Novice

Read time: 3 minutes

I am confused about the issue of “burning” or “scorching” chocolate. It is widely advised that when melting chocolate for tempering, one should not let it get above 120º F or else the chocolate will be irreparably damaged and will not be able to be tempered. However, while grinding in the melanger the chocolate gets up to 140º F to 160º F (the hotter being advised as a conching temperature). How come it is not damaged at this point but it will be if reheated/remelted later? I see some people talk about tempering straight from the melanger – which means essentially cooling from >140º F straight down to 84º F or so. Is there something about the chocolate cooling and “curing” after grinding, after which point it should not be brought above 120º but if tempered from these higher temperatures right away (without cooling first) it is OK? Any insight into this discrepancy would be appreciated. Thanks.

Nice observations. When faced with contradictory facts, the key is to tease apart which fact actually isn’t one.

In short this is a false fact from the days before home chocolate melting when people really didn’t know or believe they should gently heat chocolate. And what exactly it meant to heat chocolate gently. It seems like many people would put the chocolate in a pan, put the pan on the stove (on low of course) and proceed to burn the chocolate. How?

The issue wasn’t so much that the chocolate got to 120 F or 140 F or even 180 F, it was that the surface of the pan got much hotter. As in 400-500 F. And that is more than hot enough to burn chocolate. Now, if you constantly stirred, and mixed and kept that heat distributed, there wouldn’t be an issue. But people don’t tend to do that. They let it set….and burn that layer of chocolate that is setting on the bottom of the pan.

This is why it is pretty universally suggested that you melt chocolate in a double boiler. There is nothing magical here. It’s just that 212 F, the boiling point of water, is below the temperature at which chocolate will burn.

So feel free to heat your chocolate up. You can go beyond 120 F….if you do with properly. In a water bath. A warm oven does well too since the warm air has so little heat capacity. I often set my oven to 150-170 F and put much chocolate in there. It never burns and I don’t have to fret over water being near my chocolate.

That said, a variation of this is that you MUST heat your chocolate up to 120 F when tempering. This too is also untrue. It won’t hurt anything but it isn’t necessary. The though is that you have to take it that hot to destroy all the crystals in the chocolate do you get a good temper. As anyone who has messed up tempering by going to the mid 90’s know, all your crystals are fully melted at 100 F. Anything above that is just wasting time and energy.

Level: Alchemist

Read time: 8 minutes.

Would you have a graph showing the temperatures at which type V crystals melt for different chocolates?

Part two

If you have not read last week’s answer, go ahead and read it. I’ll wait.

Good. You are up to speed? Good. Let us proceed.

One of the big problems is that different ingredients change your tempering temperatures in different ways. The more cocoa butter you have, the higher you will be able to take your chocolate. Similarly, the more sugar you have, the cooler you need to keep your chocolate. Have a look at these graphs.

Basically, the two changes cancel each other out. Which makes sense. If you have more sugar, and the added cocoa butter is constant then you have to reduce the cocoa beans which reduces the overall cocoa butter. But notice too how the data is all over the place. It isn’t really predictive. There is a general trend. That’s all. It’s because, as you know, tempering has a lot going on that affects it.

The method you use be it slab or bowl or machine. How much you are tempering has an effect due to heat loss. And your ambient temperature likewise will have an effect for that same heat loss reason.

Look. I know this isn’t really helping you learn to temper. And it can be kind of discouraging. My point in all this is that graphs are not practical day to day.

But the general trends can be helpful. More cocoa butter gives you a higher temperature. More sugar less so. To combat more sugar, a little more cocoa butter will probably be a good idea. Those are the kind of things I want you to be able to think through.

Alright, one more thing. This last part is about the subtlety of tempering. In short it is another reason that graphs are not practical in day to day use. Recall those graphs above? Notice how although there is a general trend the data’s predictive power really kind of sucked? That is because there is another variable at work here mucking up the works.

It has everything to do with how much Type V seed you have in your working chocolate and at what temperature you are working at. Most people who work with chocolate know the word tempering. They know in general it is a process. That of making Type V crystals so that their chocolate will have a nice snap.

What many don’t realize is that while you are in the middle of tempering, lots of things are going on. From what I can tell the generally understood concept is that you are make or adding Type V seed and as long as you are holding it a the right working temperature, nothing is going on. The Type V is stable and just waiting for you to pour it into molds.

But that isn’t the case. Double negative alert. Nothing never happens.

And I bet you have seen this. You are at the perfect 89 F. You are keeping it right there. You are pouring your chocolate into molds. You go back for the next ladle full…..and the chocolate is thicker. You check your temperature. Yep, still 89 F. Did you get water in it? What’s wrong? It was working perfect, now it isn’t. You rush to finish only to find you last bars bloomed because you had to over work them.

What happened and what could you have done? The answer lies in the fact that (get ready for it) nothing wasn’t happening. i.e. something was happening in your bowl even if you didn’t see it. What was happening was that you set up the perfect conditions (like you want to) for Type V crystals to form. So they formed and your chocolate got thicker.

What could you have done?

As sacrilegious as it sounds, you need at that point to heat up your chocolate and start destroying some of the Type V crystals. There really can be too much of a good thing and thick chocolate while you are tempering is the demonstration of that.

But remember, nothing is never happening. As you heat up your chocolate (say 0.5 F BTW) you start to destroy some Type V. But recall, you also have perfect conditions to form Type V. So even though you getting rid of some, you are also forming some. The key is that those rates are different.

Analogy time. You are building a stack of blocks in the back of a moving van. That is your job. You can’t stop. Soon the stack gets too high and they can’t moved around without them falling apart (i.e. molding up with streaking because the chocolate is thick). So you need to some else to take some blocks off while you keep building (because you can’t do nothing). So Bob (your uncle) starts to unstack blocks on the really tall stacks while you keep adding more on. He is removing, you are adding. As long as he doesn’t work faster than you (you don’t get the temperature too hot) all is fine. There are plenty of stacks for you both to work on.

Now here is the key. When do you put Bob to work? If you put him to work too early (have too warm a temperature) tearing down blocks, while your stacks are small, it might be he would not let you form any at stacks (Type V) at all. If you put him to work too late your stacks are too big and unwieldy (the chocolate is too thick).

This is why tempering temperatures vary too. They are time dependent and also vary depending on how big your stacks are. Your goal is to find the sweet spot where you are building and Bob is tearing down while you have a bunch of stacks that are not too big. Sometimes you have to heat things up to make Bob work faster, sometime you need to cool things down if Bob is out pacing you.

This is why tempering machines (AT THE RIGHT TEMPERATURE) work so well. They are working in that sweet spot. Building and tearing down at just the right pace.

Let’s bring this all together now. You can see now why those temperature points were all over the place and at some points even higher when they should have been lower. It was related to how long the session was and how much Type V was there initially. A temperature that would ruin your temper at the beginning (say 90 f) might well be needed by the end because you have crystalized more Type V and need to reduce amount some so it can remain workable.

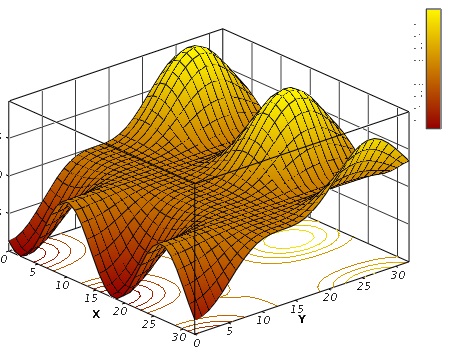

Basically maximum or optimum tempering temperature is a moving target and simply cannot be plotted on a 2 dimensional graph. You might get somewhere plotting 3D like this:

But in reality you are probably going to need something with 5 or more variable to do it justice

I don’t think so!

My suggestion is just live with knowing it’s in the high 80’s to low 90’s and go from there. It’s what all those graphs boil down to anyway.

Good luck and happy chocolate making.

The queue is current empty.

Send in your Ask the Alchemist questions to questions@chocolatealchemy.com

Would you have a graph showing the temperatures at which type V crystals melt for different chocolates?

I get this or some variation of this question once a month it seems. It is totally understandable. It would be really great to know that if you have a 60% chocolate, you look it up on a chart, and find you can always take it to exactly 87.6 F without having it bloom later.

Unfortunately it is also completely impossible to produce for a lot of reasons.

There three main reasons.

- Different cocoa beans contain different amounts of cocoa butter

- Different cocoa beans contain different types of cocoa butter

- You have no good way to know those exact amounts.

What this means is that a 60% chocolate made from beans from Peru will have a different amount of cocoa butter (what is getting tempered) than a 60% from the Ivory Coast. The former bean may have 50% cocoa butter but the later 57%. That right there will change the maximum tempering temperature.

Different amounts of cocoa butter change your tempering temperatures.

But even if we get rid of that variable it still will not help us. Let’s say we are told the cocoa butter percentage, and press out single origin butter to add back so they are the same amount, then you still can find that the 60% chocolates have different maximum melting points.

The reason is that all cocoa butter is not created equal.

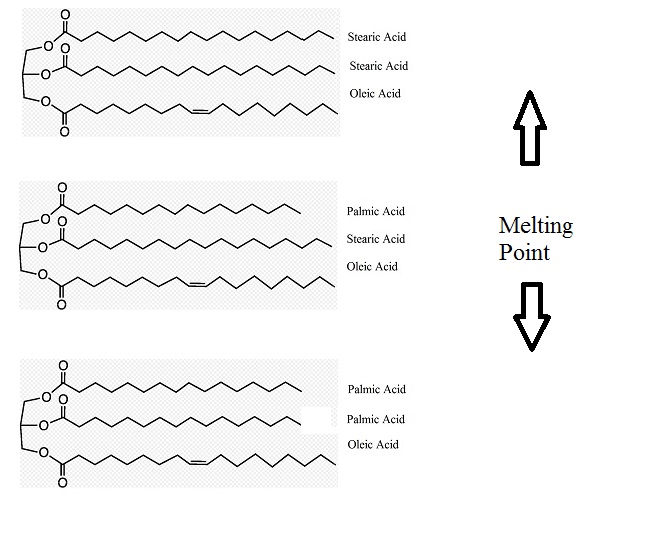

I have to resort to a bit of basic chemistry. In its simplest form, cocoa butter is made up of three parts (fatty acids). Each part can be one of 7 different fatty acids (although 3 commons ones are used 95% of the time). The longer the fatty acid, the higher the melting point.

Look at the three examples of what cocoa butter can be made up of.

Notice the difference? How as you go down, the parts get longer? As that happens the melting point goes up.

That fact right there, coupled with having no way to find out just what combination you cocoa butter has defeats us if we try and build a graph. If you cocoa butter has more of the first type, you melting point will be lower than if it has more of the third type.

How much lower? Probably about 2 F. Which is why there is always a range when giving tempering instructions. ‘raise to 87-89 F’.

On the other hand, if you are talking about just one bean and different percentages of sugar and cocoa butter, now that can be graphed. But you have to do it yourself for it is unique to your recipe and cocoa bean.

And I am going to talk about that next week, and why in reality if you do it you may find it less than helpful. Stay tuned.

And always

Send in your Ask the Alchemist questions to questions@chocolatealchemy.com

"As I understand it, when one fills a mold, the chocolate, which is at working temperature, contains predominantly Type V crystals. As its temperature drops, what keeps the undesirable crystals from forming?"

Nothing. I bet that was not the answer you were expecting. Of course, I will explain. It actually allows me to dig a little deeper into what is tempering.

I’ve mentioned before there is something called degree of temper. It is a measure of how much your chocolate is tempered. To review, many think of chocolate temper in a binary sense. It is either tempered or it isn’t. Off or on. 0 or 1. Tempered or bloomed. And that is a handy model. But it isn’t the whole truth. It is more like a number line. Negative numbers are bloom (crystals other than Type V). Positive numbers are temper (lots of Type V). And there is even a zero where there is no crystal structure at all. Like glass. It is what we call amorphous.

The higher the number, the greater the temper. That means that there is more Type V crystal. If you follow that train of thought that means for some tempers there is something else. That something else is Types I-IV. So, see, that is what I mean by ‘nothing’ keeps those ‘undesirables’ from forming. They do form. But only in small amounts. So maybe there is a better question.

Why don’t those undesirable crystals cause bloom?

Scaffolding. Seed. It is the same mechanism that lets seed tempering work. Namely that if given no direction cocoa butter will randomly form. If you give it just a little direction, it will stack up appropriately. So if you have Type V in there, that is the scaffolding that the rest of the cocoa butter will build upon. In the most technical sense there is some Type IV in there in the tiny spaces that there is not Type V seed. That ratio of V:IV is degree of temper. The more IV there is, the softer the temper. At some point that I don't know, the type IV disrupts the framework of the Type V and you get bloom.

In essence the Type V out competes the undesirables. With seed the Type V hits the ground running as it were and uses up available cocoa butter to build more Type V. If everything goes right, it’s is all used up by the time the temperature is low enough for Type IV to start forming.

Since we are talking seed, picture this as a garden. If you prepare a bed you can either direct seed a plant or transplant a growing seedling. Experience tells you the seedling will do better. It has a head start. The seeds have a tougher go as they have to out compete the weeds. If you don’t weed then the weeds can win and your seedling dies and your chocolate blooms. But if you can get your seedlings established and healthy with will use up the nutrients (think free cocoa butter) faster than the weeds and win the race (to mix metaphors).

So your goal is to nuture a good crop of Type V so it can ‘grow’ into healthy tempered chocolate before the Type IV weeds can take over. You do this by starting with a good amount of seed (seedlings) and keeping the temperature high enough so Type IV can’t form (weeding).

Finally, it is worth noting that sometimes there can be too much of a good thing. Just like you can have too many seedlings in a given area and you need to thin them for the betterment of the whole area, it is possible to get too much seed in your working chocolate. If you have been working with your chocolate a long time (it’s all relative) and you notice it thickening up, then that is what you are seeing. Too much seed. You need to thin. And you thin by heating the chocolate up a little bit (just 0.5-1 F for instance). And just like thinning kills some of the plants you actually want, that heat will ‘kill’ some your Type V. The result will be that the chocolate will thin back down and you can keep working with it. You are not destroying all the Type V. You are just selectively thinning.

There you go. Tempering as gardening. I hope that gives you a bit more of a peek behind the curtain.

I am using a sous vide cooker to regulate my temps but I have yet to be able to temper a chocolate (55% dark milk) without the same problem this gentleman photographed in his chocolate. Small dark dots clustered together.

http://seattlefoodgeek.com/2010/12/the-strange-effects-of-tempering-chocolate-with-a-sous-vide-machine/

I tried three different routines in my sous vide for tempering. All with temps going from 119 degrees to 81 to 87-90. Tried with constant mixing by hand on bag with short soak time (5 minutes at each stage), constant mixing with long time soaking between temps (20 minutes at each stage), and no mixing with long soaks (30 minutes at each stage). All the chocolate looks like in the link above. The funny thing is when I was done filling molds (all perfectly dry at room temperature and 25% humidity room) I took the extra and put in one of those solo cups and that chocolate had the least of the black spots.

I am at a loss. Not sure what could be going wrong. Any idea? I am experimenting with various levels of mixing and various soak times at each temperature but still getting the same effect.

It funny. I love the idea and tech of a sous vide. And there are some amazing looking circulating immersion heater that I think would allow you to make your own version of the EZTemper, ala water bath. But the same thing that makes it great for that application is (I think) the same item that is causing grief with tempering.

In short, kneading or no kneading, it is really hard to get an even distribution of thick material inside a bag. If you don’t believe me, try taking a cup of shortening (butter is ok but what a waste) put it In a bag, put a drop of food coloring in it, and then try and knead the color in evenly. Maybe you can do it, but I bet you end up using your eyes a lot. Working the areas that are uneven, etc. Doing it with your eyes closed you will end up with a whole bunch of rather attractive swirls I’m willing to wager.

The issue is that even though the water surrounding bag of chocolate is an even temperature, there is just no way that the chocolate is that temperature, 100% homogeneous, in the short amount of time you are giving it. That is the first thing that struck me with Scott the Seattle food geek. He was not kneading or mixing at all. It seemed to me he was expecting the system to become homogeneous nearly instantly. He mentioned holding the chocolate at a temperature for 2 minutes. Maybe, just maybe the temperature was even throughout the chocolate. I say it was for the sake of argument (I don’t believe it for an instant). What absolutely was not even throughout was the distribution of Type V crystals.

And that right there is the crux of the entire issue. See if you can follow.

We use temperature as a way to determine if the chocolate seed is evenly distributed because we are mixing chocolate of different temperature. We are stirring the entire time. When the temperature is the same throughout, we can be confident we have distributed the seed evenly. The key here is that what is important is the distribution, NOT the temperature. The temperature is just what me measure.

Now, to be clear, temperatures ARE important. The seed will be destroyed if it gets too hot. I’m just saying it isn’t the only thing that is important.

Wen I was In the lab, and we were mixing up water solutions, the rule of thumb was to invert and swirl them 10 times. That is a lot of mixing. Stirring with a stir plate often took 10 minutes. It too that long for particles to REALLY distribute well. Heck, it is why sous vide circulate. And why what is in that sealed bag in the sous vide can’t be even in 2 minutes – there is no circulation in the bag. If anything, it is inhibiting circulation.

To make a sous vide work for temperature I suspect you would need to hold each temperature for 60-120 minutes to be sure, hand kneading 6-8 times throughout. That seems like a lot of work for something that is supposed to be saving you work.

I want to swing back to both the referenced article and your own experience. In both cases the lower temperatures were the goal. He took his chocolate (in theory) to 84 F. You took yours to 81 F. His was clearly too warm and seed did not form. In your case, it may or may not have formed. But you ‘sin’ was that the temperature was your goal. And that is wrong. The goal is cooling until the chocolate starts to thicken. That is the indicator you are looking for that seed is formed. And for all I know, you did take it to that point and are just reporting the temperature.

The next problem is that he took it to 88 F for only 2 minutes with no mixing. The temperature (if it was true which I can’t believe with a 2 minute hold) is fine, but the lack of mixing means the seed (if it had been formed, which it was not) would not have been distributed evenly.

In your case you took it to 87-90. You pretty much have a no win situation. At 87, even with mixing (remember the colored shortening?) you most likely had cold spots where Type IV crystal were hanging out. Those lead to those spots you see. At 90, since this is milk chocolate, you are way too hot. So you had areas where no seed or crystals of any type existed. Hence the swirls and other spots.

In short, it looks to me you probably didn’t form seed. If you did form it, you either didn’t distribute it well, and/or had hot and cold spots because chocolate is thick compared to water and is damn hard to mix in a bag (corners are brutal).

How can you make it work? I’m honestly not sure. I’ve known a few people to get it to work and generally they take the slow approach. Each stage is 2-3 hours with periodic hand mixing.

At the end of the day, ‘fast sous vide’ which is what you are attempting is sort of an oxymoron. It’s just the wrong tool for the job in my mind.

I am wondering what kind of glycerides of fatty acids affect crystallization, so I search more information, but I am not sure the answer. Some article point out palmitatic acid, stearatic acid, and oleatic acid many times. Are these three fatty acids the main matter of chocolate crystal?

If you notice the tag line for Chocolate Alchemy, it is about both the Art and Science of chocolate making. Today it is science. We are going to geek out on cocoa butter. Chemical structures, what that means, how to think about them….and why all that great information only takes you so far before you have to start bringing the Art into it.

Full disclosure. I am pulling a bit of my data from Wikipedia. But it is ALSO backed up by LOTS of cross referencing. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cocoa_butter.

And fair warning. Wall of text (and a couple pictures) ahead – plus SCIENCE!

Before we really get into it we rather need to talk the same language. In my previous life I was a chemist, so this stuff is as intuitive to me as the alphabet is to you. I also know that a large proportion of people go glassy-eyed at the thought of chemistry. But really, they are just words, and to my mind (yeah, I’m biased) pretty logical. So, some working definitions and explanations. Have a look at the following chemical structure.

The first thing is that this is called a triglyceride. Tri means 3. See the three sets of ‘lines’. That is why it’s ‘tri’. Those lines are called fatty acids. Look to the far left. Those three “O” attached by other lines? That is a glycerin structure. Also called the glycerin backbone. When things (those ‘lines’ or fatty acids) are attached to the backbone it’s simply called a glyceride. Just think of it as different tenses of a word. Stand vs stood. Glycerin vs glyceride. And since there are three fatty acids attached, it is a…..Tri-glyceride. The layman’s term for this is fat or butter (if it is solid at room temperature) or oil (if it is a liquid). It’s generally called a fat if it is derived from an animal and a butter if from a plant source. Hence cocoa butter. A room temperature ‘butter’ from the cocoa plant. Nice and simple.

Next, each of those fatty acids (the lines) have a different name depending on how long they are. Most of them have two names. I high and fancy standardized name, and their common name, often based on the source it was first discovered in.

From the picture above, the top fatty acid is hexadecanoic acid. It has 16 carbon atom in it (each of those jogs back and forth represent a carbon atom). Hexa means 6. Deca is 10. 10 + 6 = 16. Got it? Good. It’s also called Palmitic acid. Guess where they found it first? Yep, from the pressing of the palm kernel. Again, that simple. We are just going to use the common names.

Now, cocoa butter is not one fixed triglyceride. The picture above shows one possible triglyceride in cocoa butter. It is made up of Palmitic, Stearic and Oleic acid. One of each, in the order listed. But cocoa butter has other triglycerides (BTW, in the literature they are also called TriAcylGlycerides or TAG). To state it again, cocoa butter is a mixture of different TAGs. For ease of reference and reading, it is often referred (in context) as PSO. Just the first letter of each fatty acid. Have a look at this table.

There are 6 named “common” fatty acids plus the catch all ‘other’. Just from crunching some numbers (6 3 : 6 for the 6 fatty acids, 3 for the ‘tri’) there are 216 possible ‘common’ (meaning I excluded the ‘other’) TAGs in cocoa butter. In reality it is actually much less – thank goodness. Mostly there is POP, POS and SOS with smaller amounts of PLP, POO, PLS, and SOO. 216 down to 7. But from a chemistry standpoint, that is A LOT! Why do we care? Because each fatty acid has a different melting point and each combination (each TAG) has a different melting point and the proportion of those TAGs causes each cocoa butter to have a different melting point.

And THAT is why tempering is aggravating to so many people. Because each cocoa butter has the possibility to have a different TAG mix and therefore a different melting point. In point of fact, that we can temper cocoa butter at all is pretty damn amazing once you see just how many structures there are for us to work with. This is why tempering temperatures are given in ranges. Because cocoa butters come in different ranges.

Let’s look at a couple simple examples and delve into the chemistry a little so you hopefully can appreciate it, maybe understand it a little, and with a tiny bit of luck, see what you can do with that knowledge in a practical sense if you so desire.

Fact: the length of the carbon chain (C16 for Palmitic acid) is proportional to it’s melting point. C16 will melt at a lower temperature than C18 (Stearic Acid).

Why? Analogy time. You have three people holding hands and you have 10 people hold hands. Melting is getting everybody to let go. If you have to do it, which takes more energy (heat)? 10 people of course because there are more of them. It’s that simple.

But it isn’t THAT simple. That is true for straight chain fatty acids. But look at Oleic acid. See that extra line in there? It’s called a double bond ? Don’t freak out. It’s just a word. It means one of the people is holding onto something (a chocolate bar?) and can’t use both hands to hold together. The result is it takes you less energy to get them to let go (or melt).

That means that Palmitic acid (C16) melts before Stearic acid (C18).

Both Stearic and Oleic acid are C18. But Oleic has a double bond so it will melt sooner. If we look at the data of melting points, that is exactly what we see.

Palmitic 62.9 °C /145.2 °F

Stearic 69.3 °C /159.7 °F

Oleic 13.5 °C /56.0 °F

And how about if we look at Linoleic acid. It has 18 carbons but TWO double bonds. Both hands are full of chocolate! That is going to melt really easy. And indeed it does.

−5 °C /23 °F) to −12 °C /10 °F. (it’s a range depending on how it crystallizes (sound familiar?)

Bringing this all together, this means if your cocoa butter has a lot of TAGs with Oleic acid in it then it will melt at a lower temperature and you will have to temper it cooler than ‘normal’. And if it has a larger than normal proportion of Linoleic acid it’s going to really melt at a lower temperature. And if those percentages are higher, than your chocolate will tend to melt at a higher melting point.

So what does it all mean? Does it help you temper your chocolate? No, not really. It just helps you have some understanding as to some of the reasons that the chocolate you made from this year’s cocoa beans from Peru are not acting like last year’s. In point of fact, that quite often it DOES temper the same is somewhat amazing and miraculous given how small changes in TAG composition can affect just the basic melting point.

And we have not (nor are we really) even talked about how different TAG compositions crystallize together. Each different TAG will pack differently depending what other TAG is near it. And different packings mean different final structures, and those final structures are what we term the different polymorphic structures of cocoa butter. Our goal being Type V. But as you can start to appreciate now, just by the reality of different TAG being made up by different fatty acids in different proportions, they are a near infinite versions of Type V crystals. It is a whole RANGE of structures that are similar but not exactly the same. I mean how can they be the same when you can have cocoa butter with POP, POS, and SOO, TAG’s of all different lengths. I can’t be the same, therefore it has to be different or a RANGE of structures that behave and look similar!!

Confused? Yeah, that was a lot. What can you do with it? Well, If you are not adverse to it, you now have the tools to change something things systematically.

You may have heard about other oils and fats being added to chocolate. Yes, sometimes it is for financial reasons. Cocoa butter is expensive. But sometimes it is being done to change the melting point and therefore the tempering properties of the chocolate.

You have a chocolate that is just not holding temper? It melts too low? Well, have a look above. What melts higher? Palmitic acid does. And recall, it was named for being from palm oil. How about adding some palm oil? Sure, let’s look it up.

The palm oil TAG is still a mixture, but a lot of it is PPO and that will raise the melting point a bit.

How about palm kernel oil? Well, it has a bunch of Lauric acid that is C12 so that is going to make your chocolate melt at even a lower temperature.

Coconut oil I hear someone asking about. Well that is a funny one. Again, lots of Lauric acid (c12) but there are also C10 and C8 in there and when coconut oil is added to chocolate what you end up getting is a chocolate that does not bloom. Great you say? Well, no. It is also very soft (lower melting point) and does not temper either. Just because something does not bloom does not mean it tempers. It can do nothing. Sort of like a number line. To the right of zero is positive and that is tempered, left of zero is negative and is bloom…but there is still zero. Untempered. Coconut oil (in sufficient amounts) inhibits the polymorphic crystallization of cocoa butter.

At some point I want to experiment with small amounts of shea butter. It’s primary TAG is SOO. From all of our discussions here you would expect it to melt very low, but it doesn’t. Now, it’s not breaking any rules. Shea butter extract is a complex butter that in has many non-TAG (they are called nonsaponifiable) components that raise the melting point. To a surprising degree too. 89-100 F for regular shea butter and a special high melting point one that melts at 104 to 113°F.

I’ve found references it is tempering compatible (unlike coconut oil). There was a PhD research position I heard about a couple years ago where the goal was to come up with a ‘new’ form of tempered chocolate that would be more resistant to melting but still retain it’s nice mouth feel. I can see this is the direction the research would have to take. Very minor additions of select TAGs that give a shove the range of Type V crystal to the upper end.

Finally, I want to put the disclaimer in that I’m not advocating or against additions to chocolate. I’m neutral. The whole point of this conversation was to open your mind to possibilities and give a peek inside of some of the chemistry. I find understanding things terribly exciting.

Send in your Ask the Alchemist questions to questions@chocolatealchemy.com

I’m doing raw chocolate, that comes out really really good. The only thing is, that even though I do very proper tempering, after being out the fridge a bit, it will soften, hence will not keep firm on the shelf. I wonder if it’s because I use paste and butter, vs bean to bar (via a stone grinder)? Does bean to bar temper better? Is there any butter added to beans when doing bean to bar? The texture, snap, crunch etc I get are amazing once out of the fridge and maybe a few minutes out, yet more than a few minutes, all that texture is gone, and chocolate becomes soft.

I get this question or some variation a few times a month. The main issue here is misconception that whatever is being done is producing a temper. To say “I am doing a proper temper” and following up with ‘it will soften” or bloom, etc is contradictory.

If the chocolate was tempered it would not be soft at room temperature and would not bloom. It’s basically a definition thing.

It does not matter in the least how the bar looks or feels or tastes coming out of the refrigerator. All chocolate is hard and brittle when cold. The whole key about tempering is that it remains hard, glossy and brittle (has good snap) when at room temperature.

In short, it is clear your chocolate is not tempered. As to why, there isn’t enough information to say. I suspect it is just the lack of seed or the wrong temperatures. There is not a lot more it can be.

What I can say is it does not really have anything to do with it not being bean to bar. It might (or might not) have something to do with your chocolate being raw. Many raw chocolates are higher in moisture which can inhibit proper crystallization and thus temper. Likewise, butter can be added to bean to bar chocolate but it does not have to be. It is totally optional.

Much like last week’s question, the real key here is observing what is really going on and diagnosing the problem correctly. “It’s tempered but”….as soon as you put that qualifier in there (“but”) that contradicts your previous statement it should raise a red flag that something is wrong with your initial assessment of the situation. I don’t mean to nitpick. My goal is get you to realize that your chocolate isn’t tempering and that is where your problem is in all likelihood. Once that realization is made, troubleshooting on your own “problems in tempering in the Big G” becomes almost trivial.That said, I’m always here to help and I’ll be touching base personally about this issue to get your situation all fixed up.

"Have you tried the EZ Temper and how in the world does it work? I don't understand it."

Yes, I've have one (Thank you Kerry). You can go read the Review. It outlines what I think of it, how it works and the theory behind it.

The short of it is it works and I like it. Get one if you want to make your tempering life easier. It's well named.

Send in your Ask the Alchemist questions to questions@chocolatealchemy.com

My question is im trying to make a milk chocolate bar following your recipe but i substitute the cocoa butter ,for coconut oil about 8 oz and 8oz grass fed ghee. In total 16oz of fat. Now i see the chocolate more liquid. Is the coconut oil spoil the tempering of the chocolate? Could adding moré milk powder help? Just experimenting.

I am going to assume you are using this recipe:

- 2.0 lb Jamaican Cocoa beans

- 22 oz Cocoa butter

- 1 t lecithin

- 12 oz powdered dry milk (yes, this is what the professionals use)

- 32 oz sugar

Coconut oil melts at 76 F. That right there pretty much explains why you are seeing the chocolate act more as a liquid. When the chocolate should be a solid (anywhere under 79 F) the coconut oil is depressing the overall melting point. Ghee on the other hand melts around 95 F. You might think and hope that would counteract the coconut oil and ‘average out’ but unfortunately that isn’t the case and what you are see is what you get - a ‘chocolate’ that is much less viscous, thinner, and melts at a much lower temperature. .

Many oils can be used along with cocoa butter and not affect the tempering much. But coconut oil isn’t one of them. This page lays it out pretty well.

- Palm oil or coconut oil based and normally contains lauric fatty acids.

- Does not require tempering.

- Lauric fat in the presence of enzymes like lipase (found in cocoa beans), under the right conditions (moisture, temperature), can react and produce a soapy off-note.

- Not compatible with cocoa butter, although can be mixed in at a low percentage.

The really important thing here is the ‘not compatible’ part. It means it inhibits tempering.

What you used was a CBS or cocoa butter substitute. On the surface that sounds good, but what you really want and need if you want your chocolate to act like chocolate is a CBE or cocoa butter equivalent. The short list of those oils are shea, illipe, and sal nut oils as well as palm, mango kernel fat and palm oil.

There is also a class of fats and oils classified as CBR or cocoa butter replacers. They are non-lauric containing fats like palm oil, soybean oil, rapeseed oil and cottonseed oil. They sort of meet in the middle. They do not require tempering and are partially compatible with cocoa butter. “Partially compatible” – that’s another way of saying it depends on how much you use as to whether your tempering will still be possible.

Going back to your recipe, your addition of the ghee might allow you at least have a chocolate product that solidifies at room temperature, but I’m really not sure. Adding more milk powder is where I would start but it may be that all you end up with is a solid that has a very oily mouth feel.

In any case, yes, your tempering is fully ruined because you used a lot of an oil that is ‘not compatible’ with cocoa butter and inhibits tempering. There is nothing you are going to be able to do about that with the recipe as is. There just isn’t enough cocoa butter there to form a solid crystal structure. You have only about 15% where you really closer to double that AND not have other non-compatible oils (CBS) in there actively trying to thwart your efforts.

In short, add milk powder. You really have little to lose – just some milk powder.

Send in your Ask the Alchemist questions to questions@chocolatealchemy.com

This chocolate tempering has me stumped. I’m a pretty experienced candy maker. I make excellent, butter-smooth fondant, plus hard candy, spun sugar, fudge, and taffy, and am reasonably effective at re-tempering melted commercial chocolate. So I understand the crystallization characteristics of sugar, have an excellent “feel” for it. But I have had difficulty getting a feel for tempering the artisan chocolate I make from scratch.

I have been trying to temper my 8th batch, a Nacionale Maranon 75% cacao (65% bean, 10% cocoa butter), to no avail. I thought I had the process finally down. It went pretty smoothly with a Forastero batch tempered two days earlier, and had decent (though not perfect) tempers on an earlier white chocolate, a Criollo and a Trinatario. I was using more of a dark chocolate, wider temperature range on the Nacionale. It was some of my worst-blooming tempering results to date. The second time I heated it to around 129 degrees, to make sure the crystals were melted, and let it very slowly cool in a Corningware bowl, stirring frequently, to 81 degrees, then raised it to 90 degrees, and poured. (I’m just pouring it in a slab and cutting into chunks for now, not adding the complexity of molding while holding the temperature.) Both times, it set very slowly, with layers formed like sandy chocolate shale, dusted with cocoa. Without any reference data to work with, for kicks and grins, next time I will try to re-raise the temp to a lower 87-88 degrees, not 90, and see if that helps.

I have also found that certain chocolate varieties stiffen up (not just thicken) between 82 and 81 degrees, whereas another variety with the same recipe is fine taken to 81-82 degrees, can even drop to high 70s before thickening up. I’m beginning to think there is more than just the recipe, water content, and ambient temperature/seeding at play here. I can understand that the cacao fat percentage can make a difference, but when the fat range is merely 49% to 56%, that doesn’t seem like enough impact. But I suppose it might be a minor factor. And equatorial proximity is a factor.

I am sure that the initial temperature you raise it to matters a great deal. I advanced from making fairly smooth fondant to butter-smooth fondant, by simply ensuring that crystals in the cooking pan were all washed down and dissolved with water and a pastry brush, as cooking begins. This is equivalent to tempering’s initial heating to melt all the crystals, hence why I took the Nacionale up so high.

Is there any data you’ve found (or recorded yourself) correlating effective tempering temperature ranges for the different cacao varieties that you carry?

I wonder if all that complex cacao chemistry impacts the amount of each type of crystal formed, at different temperatures. If that were true, then we should be able to come up with narrower ranges by variety for pure cocoa liquor.

If that is the case, then is it reliable data across crops of the same variety? (I would guess not.) Does roasting temperature matter (once the water has been driven off) – i.e. perhaps the heat-induced chemical changes also affect temperatures at which it tempers? (Perhaps so if the varietal chemistry has an impact on tempering.)

If different brands of cocoa butter were used across batches, that would also make a difference because fat from Equatorial region cacao has a higher melting temp than that of cacaos in slightly more temperate regions. But I’ve been using the same cocoa butter lot, and predominantly cacao from fairly close to the Equator.

By the way, I have found that improperly tempered chocolate goes stale (flat tasting) much faster than properly tempered chocolate, for some peculiar reason. Hence I’m looking forward to getting this Nacionale tempered with a nice clean snap and consistent texture.

Let's see what i can do here to tease out some information. First a few corrections.

Initial temperature of melt as long as it is above about 100 F does not affect tempering at all. A clean slate is a clean slate. Likewise roasting does not affect tempering at all as long as it is a full roast and you are not leaving water in.

Chocolate and fondant are totally different types of chemistry. It's polymers vs polymorphs. The same with the sugar chemistry and polymorphs.

Ok. The rest. In some ways you are trying to see patterns where they don't exist. Or use observations for prediction. Grasping for explanations I know. What I mean is that classifying by Forastero, Trinatario and Criollo from a tempering standpoint is pretty meaningless. Those are just too broad. Frankly, even classifying by region or country does not show that great of correlation. There is some data to suggest that the closer a bean is grown to the equator the higher it's melting point. But that has not really been correlated to how that chocolate tempers. It just helps explain why different chocolates behave differently. Most likely there is a correlation, but I would not be surprised if it came down to combination of factors. Micro climate, latitude, rain fall, cultivar, etc. There is probably a great professional paper in there.

And then you get into the formulations themselves. Sugar percentage, cocoa butter added, total cocoa butter present and other ingredients. Plus a major potential contributor - water. Each of those can raise or lower the tempering ranges needed for a given batch of chocolate. The end result is too many variables and too many unknowns. At the end of the day you have to do just what you are doing. Working out individually what each batch needs and learning the feel for it. I suspect if you were able to plug in all the variables and their weighted effects, what you would end up with is a range of temperatures and a percent probability that a given temperature would work. Maybe you could tease out that this formulation needs to be brought to 80-81 F to seed and 88-89F to temper, and that other one should go lower to 79-80 F and should only be brought to 87-88 F, but at the end, all you end up with is the same pretty standard range is generally accepted.

That all said, I want to offer up some suggestions where I think you might have gone wrong with the Maranon....not because it is Maranon, but just from what you wrote and did. You heated to 129 F. That is total overkill. We are talking a couple degrees here or there in loosing temper. It's why going to 94F for any length of time in your final step destroys your temper. You are getting rid of all the Type IV and V. No matter the formulation, water content or latitude. 100 F is fine. That said, you didn't hurt anything. You just wasted a bit of time heating and cooling more than you needed.

You then brought it down to 81 F. This might or might not be your first issue. The big question is 'Did the chocolate start to thicken?'. All lovely, complicated equations aside, it all comes down to a state change. You cool until it thickens (just barely). The temperature range is only a guide so you know you are getting close and don't end up with a solidified mess. And it is only a 'mess' because it is difficult to work with, not because it does not work. If it did thicken, we can eliminate that as an issue. If it didn't, then it is very possible you didn't for enough Type IV crystals and needed to cool further.

Next you heated it to 90 F and let it cool very slowly. Personally I think this step, regardless of the previous one, probably doomed you. 90 F is high for almost any chocolate. You can go that hot, but you have to cool relatively quickly or be working with a solidly seeded chocolate. And you did just the opposite. The perfect one-two knock out punch. Tempering is a a process ( as you know). It is crystallization. It's almost a living thing. Temper waxes and wanes. It's constantly changing during your tempering batch. And maybe that is a good way to think about it. The Mojave. You could survive at 100 F for a couple days. At 110 F maybe only a day. And should it get to 125 F you only might make it a couple hours. There is an inverse relationship to your survival and how hot it is. But you can also recover. You can go to 125 F for one hour, back into the shade at 110 F for another few hours, and back into the 125 for another hour. And you can keep doing it over and over....until you finally wear out your reserves and perish, maybe only at 100 F because you have so taxed yourself at those higher temperatures. (quick side note clarification - you are only 'killing' your temper, NOT your chocolate). And to link up the analogy, your seed formed at 81 F is your water reserve in the desert. If you didn't make enough, you die sooner. If you made lots (you took it low enough or are using seed) you have more time to work and can survive higher temperatures. So what you did was take it high, and left it high, maybe with enough reserve or maybe not. Probably not since it bloomed.

In regards to trying 87-88 F for 'kicks and grins' the next time, that is exactly what you should do. As I hope you now see. But it should not be 'without any reference or data'. There is LOTS of data and references. 90 F is the upper end. You lost temper. The ONLY direction to take is down. And should you find that does not work, you look at your seeding temperature (making sure it started to thicken). Really, assuming you have low water chocolate with an average composition, there are only two places to troubleshoot a failed temper. Did you form seed (did it thicken) and did you not get too hot (ok, three - did you get hot enough to create form V, but that isn't an issue here) for too long.

So put aside type, origin, latitude and all that and focus on what the chocolate is telling you.

All those things are just there to explain why different chocolates require tempering temperatures, NOT to predict them.

Cool until it thickens, note the temperature, and then bring it up about 7-8 F.

As for the bloomed chocolate tasting flat and going stale, I would counter that is not true. It's temporary. We temper so the chocolate melts in your mouth well. Bloomed chocolate does not melt well in your mouth so the flavor is subdued.

Why can't we cool the chocolate directly to get form V crystal seeds?

That is a very good question. And when I received it, I didn't know if it was true or not. Many 'rules' we live by turn out to be myths and we do what we do because that is how it's always been done. Or sometimes it is simply the most expedient way to do them. Maybe, I thought, it was possible to form Type V crystals direct. Assuming it was, why would it not be done that way. The only reasonable explanation I could come up with was the rate of reaction, or basically how fast it takes the crystal structure to form.

With that hypothesis in mind, I set up a few tests to test the theory.

It was really simply really. I melted a few pounds of dark chocolate, set my tempering machine to 88 F, and just let it go. I took pairs of samples out at various intervals. 30 minutes, 1 hour, 2 hours, 4 hours, 8 hours, 24 hours, 48 hours, 72 hours and 96 hours. One sample I let set up at room temperature (about 65 F), the other went into the refrigerator for fast chilling (just to see if there was an effect). I also repeated this at 86 F, 90 F, and 92 F. The results? 100% bloomed chocolate. To me that is a very definitive result that Type V crystals do not spontaneously form. If they did, they would be seed crystals and allow the lattice formation of Type V and the chocolate would not bloom.

This result was not really surprising. Otherwise it would be an accepted practice. As I thought this over, it reminded me of some of my basic chemistry lectures on transition state theory.......and I've now spent WAY too long trying to come up with neat yet comprehensible pictures or diagrams showing how I understand what is most likely going on....and I failed. It's not that it's really hard, but I can see the deer in the headlights look know if I try to put it up. So I won't bother. What you and I will have to settle for is a less accurate but hopefully more comprehensible description. And my favorite...analogy.

Basically, it Type V is not stable. It's sort of a definition thing. Things like to be stable. Generally that means given the option, they will go to the lowest energy state. Since chocolate left to it's own devices does not spontaneous temper (form Type V) but instead blooms, the bloomed state must be the stable one. Since it is the stable one, and since tempered chocolate can bloom without intervention, tempered chocolate is the opposite, or unstable.